Army, Private 1st Class

Joseph P. Minnock

DATE OF BIRTH

January 19, 1947

DATE OF DEATH

November 6, 1965

MEMORIALIZED AT

Beverly National Cemetery, Beverly, NJ

SPONSORED BY

Memorial Day Parade Committee

Written by Don Sweeney and research by Stu Rosenthal

A casual portrait of the teenaged Joe in the persona of the warm-hearted tough guy, that made him endeared by all that knew him.

Private Joe Minnock, likely at Fort Dix, NJ, following completion of basic training (est. March 1965). This photo was obtained from his family who probably snapped it right after his graduation ceremony.

Private Joseph P. Minnock was trained as a military parachutist. Joe Minnock earned the parachutist badge, or ‘Jump Wings,’ following completion of jump school.

Camp Radcliff served as a U.S. Army helipad in An Khe, Vietnam, in the mid-1960s. Also known as the ‘golf course,’ it was also base camp for Joe Minnock during Sep-Oct 1965.

U.S. troops had to move particularly fast in landing zones, or open areas in combat where they would rendezvous with friendly helicopters that were vulnerable to enemy fire.

Joseph P. Minnock is interred at Beverly National Cemetery, Beverly, NJ along with his mom and dad.

In November 1965, Cranford conducted its annual Veterans Day ceremonies, but the events were overshadowed by devastating news. On Nov. 8th, national news outlets told of a horrific ambush and firefight involving U.S. soldiers in the central highlands of Vietnam. Sadly, a telegram had just arrived at the Mohawk Drive home of James and Theresa Minnock, informing them that their youngest son, Joseph, was among those killed in the battle. On Nov. 10th, the day before Veterans Day, the front-page headline in the local Cranford Citizen and Chronicle newspaper said that Minnock was the ‘First Local Vietnam Casualty.’ It was the first local military loss since the Korean War and would later be followed by several more service-related deaths from Cranford during the Vietnam War.

Private Joe Minnock, likely at Fort Dix, NJ, following completion of basic training (est. March 1965). This photo was obtained from his family who probably snapped it right after his graduation ceremony.

Fast forward to 2018, when we teamed up with TV35, the local public access channel, to create short videos about the fallen men featured in the Cranford 86 Hometown Hero project. Among the 16 clips produced so far, the Joseph Minnock video is the one featured first. However, the way we featured Joe in that video, and back in the inaugural 2016 article, is rather different than how we approach our stories today.

Early on, I would simply interview friends and family members who knew these men and could share stories. I had no previous research experience and was unaware of the many websites and research portals we now routinely use. In fact, for the original Joe Minnock story, I had no photograph, something that we now strive to obtain before we begin a draft. Days before the 2018 Memorial Day ceremony, when we introduced a new banner honoring Joe Minnock, we scrambled to locate even the most tattered photograph to imprint on the banner. That photo is available on our website, Cranford86.org, and accompanies our original article about Minnock (which was combined with the Ray Ashnault story).

Still, the Joe Minnock profile left us unfulfilled because of the incomplete storyline and obscure photograph. One evening, Stu, now our lead researcher, scoured the deep web and our databases for additional information. He determined that Joe’s older brother, James, had relocated to Utah years ago. James has since passed, but Stu reasoned that James had a son, also named Joseph, born shortly after his brother’s death. We recently contacted Joseph E. Minnock, a respected Utah attorney, seeking information or pictures about his namesake uncle. He promptly responded and shared several portraits of his Uncle Joe, including a much-improved version of the original image depicting Joe sitting in front of a draped parachute. It was his Army jump school graduation picture. He also told us about Mike Smith, Joe’s cousin and best friend whom we contacted. The door to knowing Joseph Minnock was about to open wider.

Mike Smith told us of his inseparable relationship with Joe Minnock of Cranford – they were cousins who “played hard” on the shores of The Raritan Bay in Lawrence Harbor each summer. According to Mike, Joe idolized his Scottish father – a career soldier and war veteran. Joe sought to follow in his footsteps, and those of his older brother, James, also a soldier.

Through interviews and research, our team often uncovers the personality or complex character of our subject hero. Friends and people who knew Joe Minnock generally remembered him as a nice kid, but perhaps intimidating to outsiders. We spoke to Patricia Castaldo Hobie, a teacher who knew Joe in high school. She recalled a warm soul – a truly nice person. Next, we contacted classmate Kevin Cheiff (CHS 1967), after locating his tribute to Joe on a veteran’s website. According to Kevin, Joe wore “different” clothes than most kids – tight legged jeans that he cuffed short at the ankle to expose white crew socks. Joe’s shoes had cleats on the heels, which distinctly clicked when he walked the hallways of Hillside Ave. School. Because Joe was a couple years older than his classmates, he could appear big or intimidating. He carried a tough guy persona, which he acquired as a younger kid in Newark. Joe was different than the average Cranford kid, and Kevin said that no one bothered you if you were friends with him. Kirk Foltz, had the proof.

We spoke with Kirk, another classmate and close friend, who likened Joe to the John Milner character in American Graffiti: a flashy greaser from the early 1960s with a cool car. Joe epitomized the offshoot character, Fonzie, from the television series Happy Days — a kindhearted man obscured by a tough guy shell. Kirk vividly recalled an enduring incident, and fitting conclusion to our interview. Kirk told Joe that a local bully was bothering him, to which Joe confronted the kid. After a brief interaction, that began with words but concluded differently, the matter was resolved. Kirk was never bullied again by that kid.

School was not Joe’s strong suit, and so he left in the middle of his sophomore year at the age of 17. To the shock of his peers, Joe had volunteered for the U.S. Army. He arrived at Fort Dix, NJ, in early Jan. 1965, and spent his 18th birthday in boot camp. He advanced to Fort Benning, GA, where the new infantryman was assigned to the famed 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile), also known as the ‘First Team.’ Here, Joe joined approximately 15,000 soldiers who were training in airmobility, a newer form of combat for rapid troop insertion via helicopter. The First Cavalry, which a hundred years earlier had entered the battlefield on horseback, would soon enter the Vietnam jungles on a new mount, the Bell UH-1 Iroquois (Huey) helicopter.

Camp Radcliff served as a U.S. Army helipad in An Khe, Vietnam, in the mid-1960s. Also known as the ‘golf course,’ it was also base camp for Joe Minnock during Sep-Oct 1965.

Joe had joined the Army at a time when the American government was committed to thwarting the reunification of Vietnam by communist-led North Vietnam. Several thousand American advisers and support troops had been positioned in South Vietnam for years already, but U.S. involvement would soon escalate. In early 1965, the enemy Viet Cong infiltrated the central highlands of South Vietnam, attacked and killed Americans. Newly emboldened, U.S. President Lyndon Johnson extended a ‘blank check’ to his defense staff, determined to win the war. Significantly more troops were mobilized, and by late 1965, U.S. military strength in Vietnam would swell to nearly 200,000 personnel. This would include the First Air Cavalry.

Following a brief visit home, Private Minnock embarked from Georgia on August 20th, 1965, journeying through the Panama Canal. He crossed the Pacific, with brief stops in Honolulu and Guam. Following a month-long sea voyage, Minnock and his unit reached the shores of Qui Nhon, Vietnam, on September 20th. They were immediately flown to Camp Radcliff, An Khe, a new U.S. military site located about 42 miles inland.

Radcliff became Minnock’s base camp for the next month. It was the world’s largest helipad — host to hundreds of helicopters– and was carved from dense undergrowth, bamboo and 12-foot-high ant hills. To reduce dust the men who manually cleared the brush were instructed to make its rugged terrain as a smooth as a ‘golf course.’ But it was hardly a country club, as the natural elements proved a recurring irritant, with dust, oppressive heat, downpours, rat infestations, mosquitos and malaria. Moreover, the enemy was afoot, and the twelve-mile long perimeters required constant protection from potential sniper fire or attack.

On October 19th, the enemy attacked a Special Forces camp at Plei Me (pronounced ‘Play-mee’), about 60 miles west of Radcliff. A relief force was requested from nearby Camp Holloway, Pleiku (‘Play-Q’), but this would have left Holloway undermanned and vulnerable. So, for added protection, personnel from the First Team were dispatched from Radcliff. Minnock and units of the 1st Brigade arrived via helicopter at Holloway on the night of October 23rd. The relief force could now proceed to Plei Me.

The next afternoon, Minnock and his company performed an airmobile assault near Plei Me. By the next evening, Plei Me was secure, but U.S. soldiers were wounded in the fighting. On Oct 26th, with the enemy believed in retreat, the war plan had evolved. U.S. General Westmoreland, Vietnam commander, visited Plei Me, and expanded First Air Cavalry’s mission from a reinforcement and defensive posture to an all-out offensive capability. The next morning, Minnock and several hundred men from his battalion air assaulted onto a landing zone north of Plei Me. Although unopposed, it represented the first air assault for the First Air Cavalry in Vietnam under the expanded offensive mission. For most of the next week, Minnock conducted air assaults, search and clear operations around Plei Me. His unit advanced westward, and likely experienced limited enemy encounters until the first week in November, with reports of fierce fighting and U.S. casualties.

On November 6th, the First Air Cavalry sustained its highest casualties in Vietnam to date. In the morning, a sister unit of Minnock’s, Bravo Company, was patrolling when they spotted an enemy supply squad of about 12 men. They gave chase, and at around 11am, entered a small meadow the size of a football field. Suddenly, Bravo Company became pinned down and was unable to move. Gunfire rained upon them from the surrounding forest, through the waist high elephant grass and from enemy soldiers camouflaged as bushes. Minnock was with Charlie Company, and moved in to an adjacent meadow around 1pm, trying to assist their beleaguered comrades. But even more enemy guns were unleashed onto Charlie Company, which was also now pinned down and cut off from Bravo Company.

Minnock and the estimated 340 American soldiers from the battered units had been lured into an organized ambush. They had unwittingly confronted an estimated 500-1000 enemy troops who were fresh from a local base. Surrounded, the Americans were forced to fight and dig in against a well-supplied and superior positioned enemy. “It was a nightmare,” said one sergeant, in part because of the close range fighting that prevented aerial support and medical evacuations.

Acts of bravery abounded. A lieutenant, despite wounds and paralysis, continued to direct his platoon over radio for hours. Mortally injured, one medic continued to crawl around tending to the wounded. After a grenade landed among a pair of U.S. soldiers from Minnock’s company, one of the men, Private Thomas Maynard, threw himself onto the grenade. He was posthumously recommended for the Medal of Honor.

The battle raged into the night, and not until the enemy had fallen back could medical helicopters evacuate the wounded and dead. Private First Class Joseph P. Minnock was among 26 U.S. soldiers killed, most of whom were part of his company. An estimated 121 enemy soldiers were also killed. The battle action was swiftly reported by Joseph Galloway, an embedded U.S. journalist from United Press InternationaI.

Ten days later, back in Cranford, the school flags were lowered, and Joe Minnock’s life was celebrated at St. Michael’s Church where he was a communicant. The funeral procession was led by the Cranford Police Department and an Army contingent. A bugler and firing squad from Fort Dix joined the ceremony at Beverly National Cemetery, NJ, where Joe Minnock was laid to rest on Nov. 16, 1965. Heartbroken, Joe’s parents passed away four years later, and within 12 days of one another. They were laid to rest alongside their youngest son.

The fighting where Joe died was in the vicinity of the Ia Drang Valley, Vietnam, made famous by the book and related film We Were Soldiers Once…And Young. The action, also witnessed by reporter Galloway, depicts a fifty-four hour battle, over four days, the Battle of Ia Drang, which occurred just days after Joe’s death. The book was dedicated to the memory of the 300+ U.S. soldiers who died in the broader thirty-four day Pleiku Campaign, in October and November 1965, and includes Joe Minnock. Joseph P. Minnock’s dream of following his dad and brother in service to the nation had materialized. His name is now etched in history as one of the brave souls that gave his life so that all Americans can live in freedom. He is an American patriot, and among our Cranford 86 Hometown Heroes.

Addendum

Below is additional media relevant to this story.

The UH-1 ‘Huey’ helicopter was the Army’s workhorse for airmobility in Vietnam, for transporting and rapidly inserting combat troops into the jungle. Each helicopter would carry 6 or 7 soldiers per trip, requiring numerous round trips for the low flying “Hueys” to move sometimes three or four hundred soldiers into their appointed assault targets.

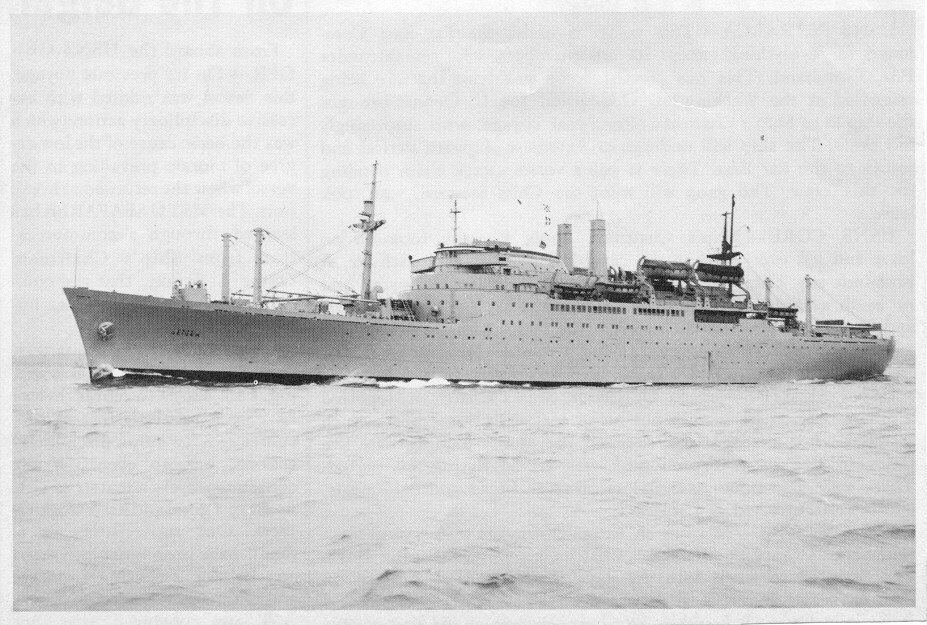

Joe Minnock traveled to Vietnam on the USNS Geiger, beginning Aug. 20, 1965. He traveled through the Panama Canal, with brief stops in Hawaii and Guam, and arrived in Vietnam on Sep. 20, 1965.

Joe Minnock was part of the Army’s legendary First Cavalry Division which, 100 years earlier, rode into combat on horseback.

The November 10 Cranford Citizen and Chronicle announcing Cranford’s first Vietnam war casualty and the events of Veteran’s Day 1965.

A 26 minute documentary on the creation of the 1st Cavalry Division, Air Mobile

A 9 minute video of first hand accounts of the battle of Ia Drang Valley