Bruce E. Nostrand

Army, 2nd Lieutenant

DATE OF BIRTH

March 4, 1919

DATE OF DEATH

March 2, 1945

MEMORIALIZED AT

Manila American Cemetery, Philippines

Meet 2LT Bruce E. Nostrand, WWII A-20 Havoc Bomber Pilot

Written and researched by Don Sweeney and Janet Cymbaluk Ashnault

The Cranford 86 Project is now into its tenth year of memorializing our town’s fallen heroes, ensuring that the names engraved on the tablets that stand at our Memorial Park on Springfield Avenue have both a face and a story. We are proud to introduce World War II pilot 2nd Lt. Bruce E. Nostrand as our 50th fallen hero profile.

Like 56 of our Cranford fallen heroes, Bruce Nostrand was a member of our “Greatest Generation”. In the Great Depression, Americans were raised during a period that taught them to do more with less. They did not let the lack of abundance be an excuse to be used for failure of completing a difficult task that lay before them. We all have heard people say that if it weren’t for the men and women of the Greatest Generation, we could have never won WWII. Our team agrees wholeheartedly with this thought as we dive into the 1940’s to tell yet another one of these incredible stories. Continuing down the honor roll left for us by Cranford’s forefathers, we note that once again, our current honoree was a member of one of the highest levels of military service. Bruce Nostrand is among at least 27 other Cranford men, who defied the odds to qualify as one of the elite airmen who occupied the cockpits of the engineering marvels that dominated the skies in WWII. We are privileged to tell his story.

Bruce Ellwood Nostrand—Early History

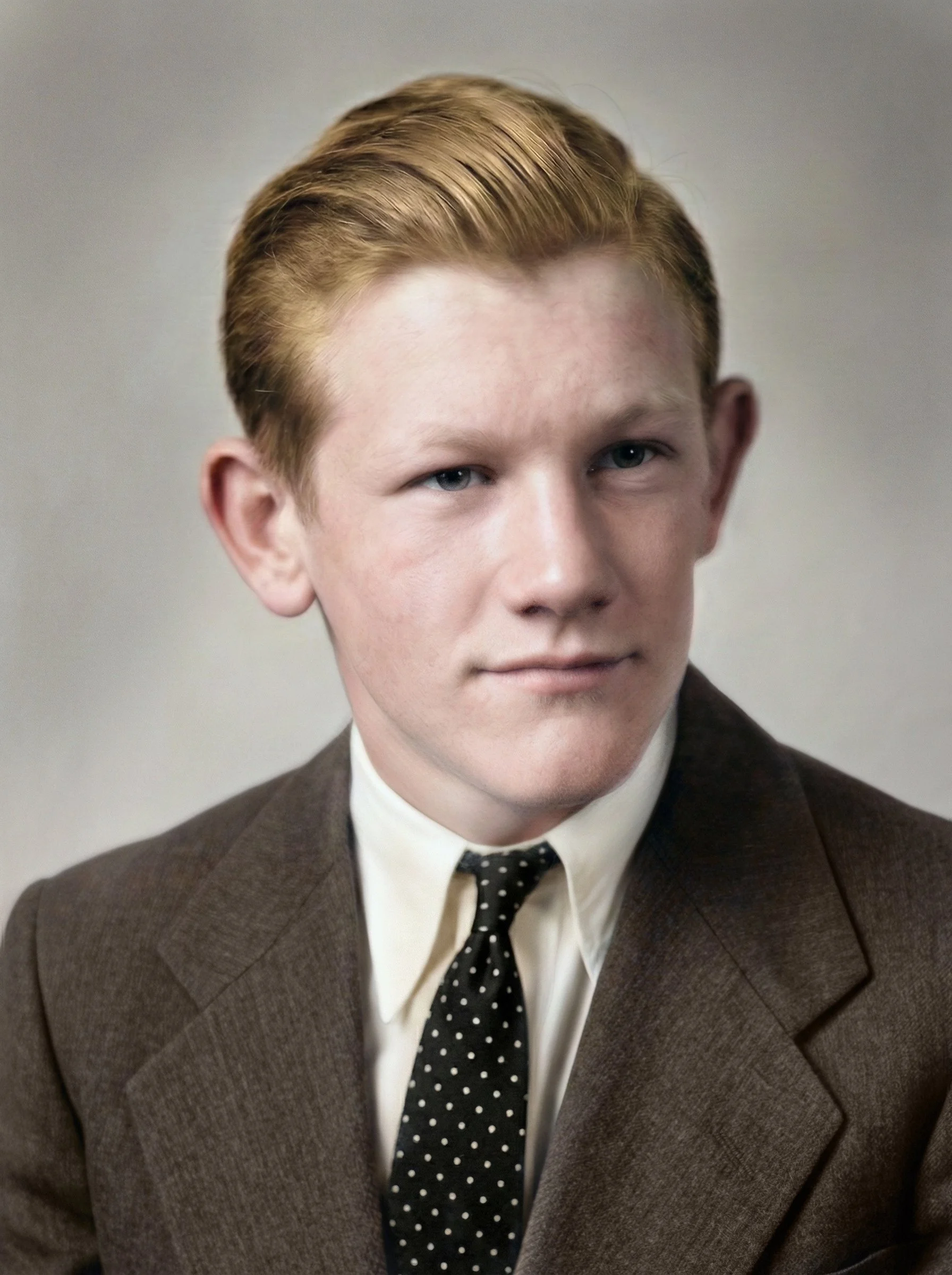

Bruce Nostrand while in elementary school in Roselle Park.

A family album photo simply labeled "Teenage Bruce at the Jersey shore"

Bruce's Roselle Park High School senior portrait.

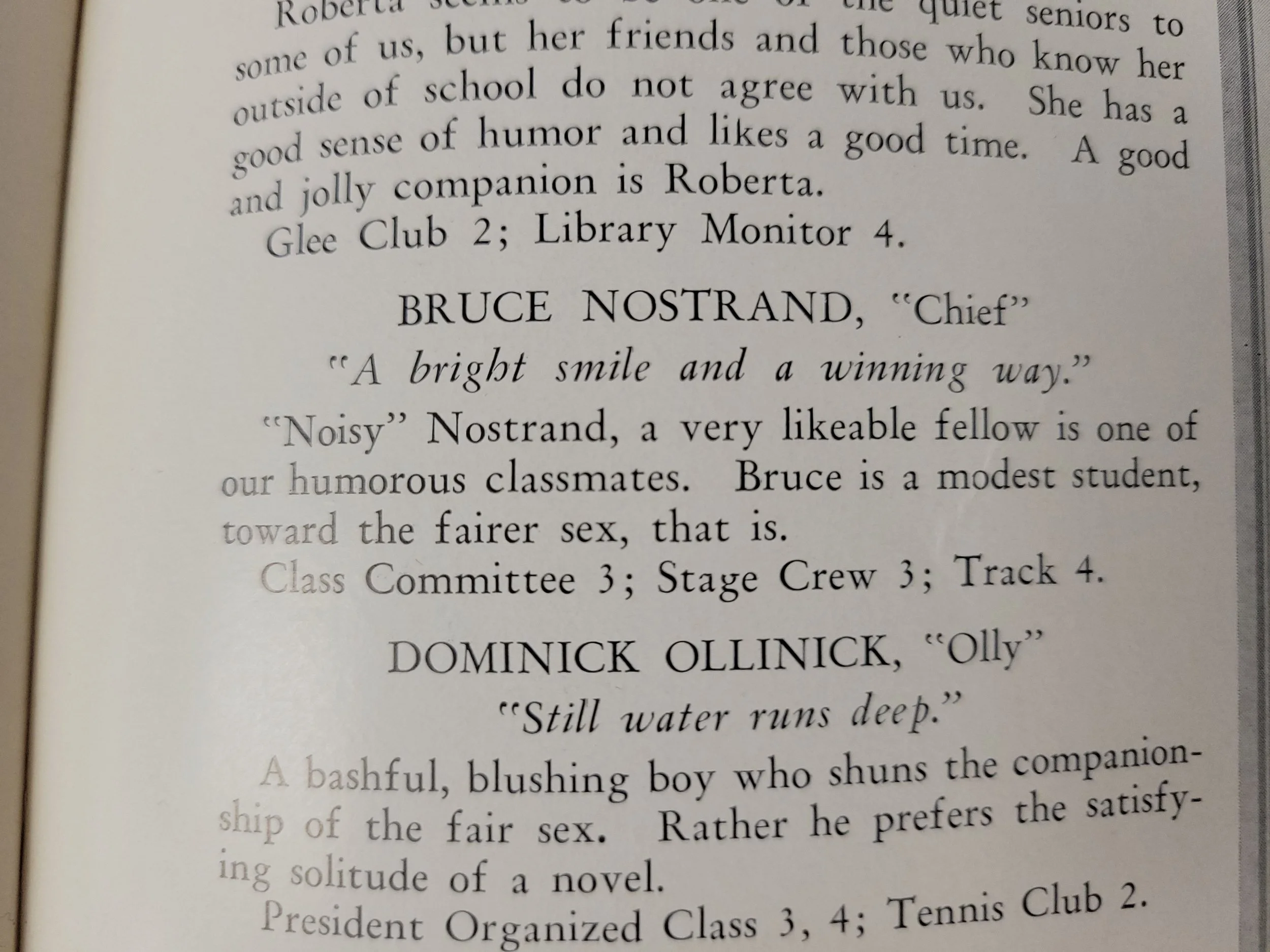

The only description we found of our hero’s demeanor. Modest around the ladies and we assume that “noisy” means quiet.

Roselle Park High School yearbook photo of Bruce, who was on the track team.

Sporting a Cranford sweater, Bruce Nostrand shows some spirit for his new town. Starting out in Kenilworth with elementary school, then Roselle Park for High School, He lived in Cranford with his younger cousins, possibly his Cougar attire is in support of his young cousin’s sporting involvement. We all know how that works.

As a young boy Bruce experienced even more adversity than the ordinary child of the Great Depression. He was born to Clarence Bradbury Nostrand and Minnie Erdle Nostrand on March 4, 1919 in Rahway, New Jersey. But, sadly, when Bruce was just four years old, his father Clarence died from unknown causes and his mother, Minnie, deemed herself unable to raise Bruce alone. Custody was given to Bruce’s grandparents John B. and Harriet in nearby Kenilworth. John B. was a poultry worker and we’ve seen his newspaper ads in the classified section, selling chickens, back in the day, from his home on 23rd Street. Note that we are using middle initials for clarification purposes, as the Nostrand family pays great homage to their ancestors, and many namesakes exist. Bruce graduated from elementary school in Kenilworth and then from Roselle Park High School in 1935. He lost his grandparents in the mid 1930’s and was taken in by his uncle, John V. Nostrand, who was just 10 years Bruce’s senior. In the 1940 census, we see that Bruce, age 20, was living with his Uncle John V. his Aunt Elizabeth, and his cousin Diane, age eight, at 4 Indian Spring Road in Cranford. Later records show the Nostrands living at 15 Hamilton Avenue.

It seems that after his high school graduation, no grass grew under Bruce Nostrand’s feet. He immediately secured employment in New York City at Manhattan Bank, where he worked for just six months before joining Western Electric in Kearny as a shipping clerk. The sports pages told us that Bruce played in his company’s tennis club. During this time, Bruce was also studying at Rutgers University in Newark after enrolling in September of 1938. In March of 1940, for reasons unknown, Bruce withdrew from Rutgers with two thirds of his studies completed. Seemingly, with a plan in mind, Bruce resigned from Western Electric in December of 1940.

Bruce Joins the Cavalry

1941 photo of twenty-one-year-old Bruce Nostrand posing in front of a tent at Fort Jackson, South Carolina, as a member of the 102nd Cavalry.

Still practicing mounted battle tactics in the 102nd Cavalry, Bruce Nostrand approaches his equine partner, preparing to start a training exercise.

The 102nd Cavalry—The Essex Troop of the New Jersey National Guard has a history that dates back to 1890, originating from Newark, New Jersey. In November of 1940 the 102nd was reorganized into a mechanized regiment, but still retained mounted units. On January 6th, 1941, for the third time in its history, the regiment was federalized and called to active duty. It was on this exact day, that Bruce E. Nostrand, walked into the National Guard Armory in Westfield, N.J. and enlisted into the United States Army. He was 21 years old, stood five feet, ten inches tall and weighed 160 pounds. Bruce’s training was based in Fort Jackson, South Carolina and the troops were warned at the outset that they were training for war, a fact which wasn’t to be taken lightly. Shortly after their arrival, new mechanized equipment rolled in, including cars, motorcycles and trucks, as well as additional horses to supplement the mounts that had been brought from New Jersey. In addition to standard military training, the troopers were also schooled in all phases of horsemanship, including mounted combat. The Pearl Harbor attack occurred towards the end of the 102nd’s 14 month training program and the needs of the U.S. military were changing rapidly. At some point, a specific potential was recognized in Bruce, and he, along with 56 others, received an appointment as a flight cadet in the Army Air Force. The college credits that he had under his belt probably helped him to be selected for this exciting opportunity. The 102nd ended up serving in North Africa and Europe and although Bruce’s photo can be found in the 102nd United States Cavalry yearbook from 1942, the path he chose took him to a very different theater of battle.

Another Path Chosen

As an Air Cadet, Bruce Nostrand in 1943.

In a great find by our researchers, we see Air Cadet Bruce Nostrand, third from left, posing on the wing of a training aircraft at flight school in Yuma, Arizona. Class 43-G, Squadron 14.

Bruce Nostrand and Dorothy Hodges enjoy each other’s company. After a short engagement they would marry and be separated by his deployment after just 4 months.

Bruce began the arduous path through flight training in early 1943 when he transferred to the Army Air Force. Through nine weeks each of Preflight, Primary, Basic and Advanced training, the cadets were tested and retested, and were in constant fear of exhibiting any sign of physical or mental shortcomings which would result in elimination from the program. Details on the challenging path to becoming a member of a flight crew have been described in the previously told stories of WWII airmen Tuttle, Prescott and McGarry. Like these other Cranford heroes, Bruce completed his Advanced Training in the desert at Yuma, Arizona, where he was at last awarded his silver wings. Our researchers were able to locate his 1943 graduation yearbook with an amazing photo of his training squadron, which we always consider a lucky find. As is customary, upon graduating from Advanced training, a new airman would be granted a 15-day leave which 2nd Lt. Bruce Nostrand spent at home, in Cranford.

A clue to Bruce Nostrand’s personality came from his high school yearbook, where he is described with “a bright smile and a winning way”, but quiet and modest, especially with the ladies. Well, flight training must do wonders for confidence, because in January of 1944, blond-haired, blue-eyed Bruce became engaged to Miss Dorothy Hodges of Dunellen, NJ. On April 15, he and Dorothy were married in Charlotte, North Carolina, where Bruce was serving as a flight instructor. The couple had just four months together before Bruce received his orders and was sent overseas to the South Pacific.

Bruce was assigned to the 312th Bombardment Group, 387th Squadron, under the 5th Air Force. The 312th was nicknamed the “Roaring 20’s” after the type of aircraft that it flew. The Douglas A-20 Havoc was an unusual, medium weight bomber attack aircraft known for its speed and maneuverability. “Havoc” referred to the chaos it created while on its high-powered, low altitude bombing and strafing runs, which had made it famous in earlier campaigns in North Africa. Unlike most big bombers of WWII, the A-20 did not use a Norden bombsite to drop bombs from a high altitude. Instead, its bombing missions were flown at much lower altitudes. Surviving eyewitnesses to A-20 attacks report being able to actually see the pilot’s faces and nose art designs as the planes came in fast and low. In order to be able to drop bombs at close range, “parafrags” were used. Parafrags were unique 24-pound explosive charges with parachutes attached. The parachutes slowed the delivery of the bombs, which allowed the aircraft enough time to leave the area before the powerful detonations occurred. The parafrag was especially useful when attacking enemy airfields. Designed to break into tiny fragments upon impact, it would shred the thin metal skins of parked aircraft, leaving behind a burning junkyard. During low altitude strafing runs in the A-20, targets would be attacked by 50 caliber machine guns and 20mm cannons. With only two occupants in the plane, the pilot would have tremendous responsibilities, acting as co-pilot, navigator, flight engineer, front gunner and bombardier. A gunner occupied a top turret and protected the skies above and to the sides of the aircraft. The large bomb bay separated the two crew members and the only communication between them was by intercom. It was a unique set up compared to every other bomber in our previously told stories.

Some History of Lt. Nostrand’s Battle Theater

Twenty-four-year-old 2nd LT Bruce Ellwood Nostrand in July of 1943, proudly wearing his officer’s uniform and silver wings, after completing his advanced flight training in Yuma, Arizona.

The Douglas A-20 was controlled by one pilot with armaments and aviation control at the pilot’s fingertips. A turret gunner flew in the A-20 as well.

A-20G Havoc displayed at the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force.

In late summer of 1944, our Cranford hero, a trained Army Air Force pilot, arrived in the South Pacific. Some historical background is necessary to better understand the situation into which he had been dropped. The attack on Pearl Harbor on the morning of December 7th, dealt a lethal blow to America’s Naval fleet, leaving it vulnerable to the waves of relentless attacks which immediately followed. On December 8th, the Imperial Japanese Navy began a rampage against American possessions throughout the South Pacific. Starting with air attacks on Wake Island, the Philippines and Guam, the carnage continued for a solid six months, mostly unanswered by the crippled Allied forces. The criticality of what was happening here cannot be understated, gaining complete control of the Pacific Theater could allow Japan the means to attack the mainland United States.

General Douglas MacArthur commanded American military operations in this part of the world from the largest collection of islands in the South Pacific, the Philippines Archipelago. The Japanese, in a methodical attack from north to south, nearly destroyed the land-based American Air Force in the region. On March 11,1942, MacArthur, under orders from Washington, escaped to Australia. He left the Philippines with the famous quote “I came through and I shall return”.

The island of Luzon is the largest and northernmost of the Philippine Islands. On Luzon, the entire American military was forced to retreat and was cornered into the island’s southernmost peninsula at Bataan. After a grim 99-day standoff, 75,000 American and Filipino soldiers were defeated and captured. What was to follow was the cruel and humiliating Bataan Death March, where prisoners were forced to march for 65 miles while subject to starvation, dehydration and harsh brutality at the hands of their Japanese captors. It was the largest surrender by an American military unit since the American Civil War at Harper’s Ferry.

On May 6, 1942, General Jonathan Wainwright, the American commanding officer in the Philippines, contacted General MacArthur by Morse code, before he waved a white flag on a mop handle in surrender of the entire territory of the Philippine Islands. Where the attack at Pearl Harbor was the most famous American defeat, many feel that the surrender of the Philippines was the low point of WWII in the Pacific Theater.

As the Philippines fell to the enemy and America was frantically trying to repair and rebuild its naval fleet, the Japanese Imperial Navy rushed to deliver what could have been a killing blow, at the Battle of the Coral Sea, off the coast of Australia. If defeated here, an American surrender in the Pacific may have become an unthinkable reality. Although the American fleet lost one aircraft carrier in this battle, the USS Lexington, and nearly a second, the Japanese fleet was forced to retreat. While considered at the time as a stalemate, looking back in history's eye, it was a turning point for the American war in the South Pacific. In what is described as the most incredible comeback in world history, with a tremendous feat of industrial production, America’s navy was being re-created in the Pacific, dwarfing the formerly dominant Japanese fleet.

As the tide began to turn in favor of the Allies, General Douglas MacArthur would return to the Philippines on October 20, 1944. A famous staged photo shows him wading in knee deep water in front of a Marine landing craft, delivering on his promise made in 1942.

Although each was an Allied victory, the battles with names such as Midway (June, 1942), Guadalcanal (November, 1942), Bismarck Sea (March, 1943), and Philippines Sea (June, 1944), left unthinkable amounts of destruction at the bottom of the Pacific. Tens of thousands of men and massive tonnages of advanced naval fighting ships were lost.

Life in the Pacific Theater of Battle

2nd Lt. Nostrand met up with his unit, the 312th Bombardment Group, in Hollandia, New Guinea, near Humboldt Bay, a deep water port. He found himself jumping midway into this aggressive campaign to regain all of the island territories that had been lost to the enemy early in the war. As the Allies began the fight for reoccupation of the Philippines, the bombing and strafing missions of the 312th served to support ground troops or destroy enemy infrastructure.

Upon arrival in Hollandia, new pilots of the 312th had to quickly learn the ropes of day-to-day military life in this primitive, foreign land. The men were responsible for constructing their own quarters, usually a wooden platform with a canvas top and plenty of mosquito netting. Bartering was a common practice and coming up with a bottle of spirits would provide you with materials needed to raise your accommodations to a 5-star level, comparably speaking. For pilots like Bruce, arriving in the early fall of 1944, the number of missions that they flew started out slowly, with roughly 10 flights per month, usually consisting of four to six A-20’s.

The pilots were offered an optimal view of Allied ships gathering in Humboldt Bay in preparation for the invasion of the Philippines. When the ships set off for Leyte Island in the Philippines, the convoy stretched across the sea to the northern horizon and for miles to the east and west, truly a sight to behold. News of a successful invasion of Leyte came on October 20, 1944.

In December of 1944 the 312th had little to no missions, as they were moving their airfield to Leyte. The ground echelon had departed in November and sailed in a convoy to the newly-liberated island. Construction of a new airstrip in Leyte began in mid-December and finally, in early January of 1945, the pilots made the trip up from New Guinea. Pilots were warned to treat the flight to Leyte as a combat mission and to prepare to be jumped by Japanese fighters originating from the southernmost Philippine island of Mindanao. As more and more islands were conquered by the Allies, Bruce moved with the 312th two more times within the Philippines.

In January and February, which is the rainy season in Leyte, the number of flights per month almost doubled. After the Allied amphibious landing in the Lingayan Gulf, on Luzon, the planes of the 312th were needed to support the troops which were driving south to Manila, as well as for neutralizing airfields on northern Luzon. For Bruce's contribution to victory in the invasion of Luzon he received the Air Medal for heroic acts and meritorious achievement during aerial flight.

Missions began with a briefing on the target by an intelligence officer followed by a rough and muddy jeep ride to the airstrip. The gunner was responsible for checking the rear compartment and turret and the crew chief would confer with the pilot describing any anomalies on the plane. Typical combat mission duration was between two and five hours and had to meet certain criteria to qualify as a combat mission.

The number of missions required to complete a pilot’s combat tour in WWII varied throughout the war. Originally, 35 missions was the quota, but the goalpost was moved frequently, depending on theater of battle, pilot shortages, etc. We believe that, in early 1945, Bruce would have needed 50 missions before he could go home.

As the Allies were steadily regaining control of the Philippines, the strategic planners began to focus on a plan to attack the main islands of Japan. The majority of troops and firepower would head north toward Okinawa, Iwo Jima and the Mariana Islands of Tinian, Saipan and Guam, where airstrips that could accommodate the B-29 Superfortresses could be secured. The 312th Bombardment Group, would be assigned to neutralize the Japanese controlled island of Formosa, approximately 275 miles to the north. Formosa, (present day Taiwan), equal in size to the state of Maryland, was no little island. The sugar cane processing plants on Formosa had been converted to create butanol, which was used to make aviation fuel. The aircraft manufacturing facilities on the island converted old planes into deadly Kamikaze flying bombs. With Formosa’s prime location off the Indochina coast, it boasted many “airdromes” or air strips to support Japanese war efforts. This island was just loaded with prime targets for the 312th, and with the A-20’s cruising speed of 300 MPH, a round trip mission could be accomplished in under three hours.

2nd Lt. Nostrand's Last Mission

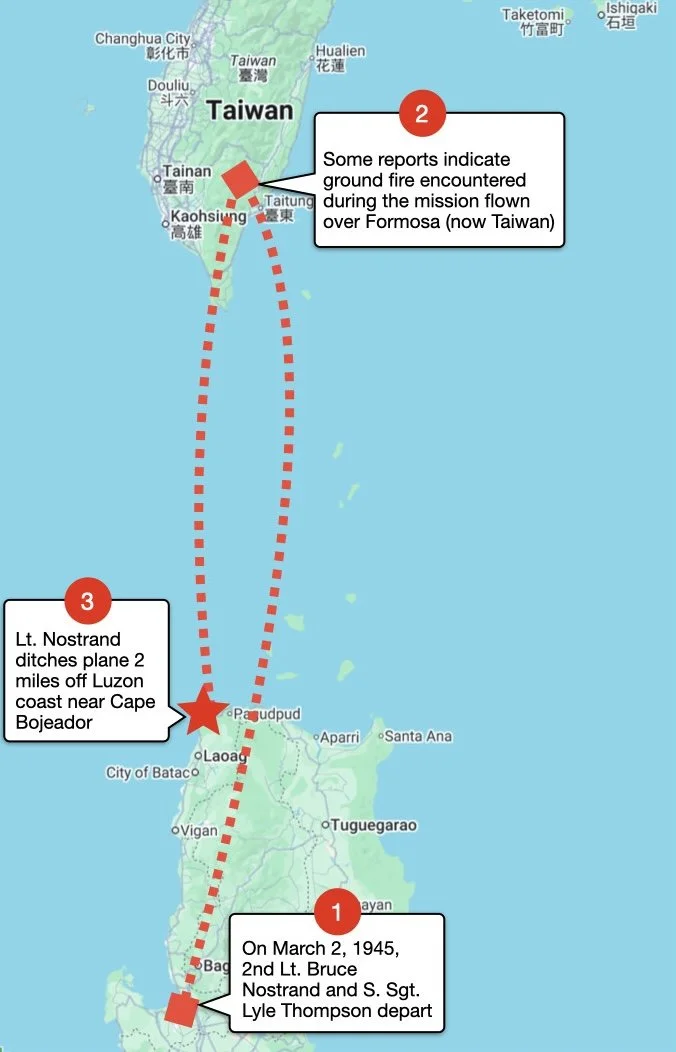

Bruce Nostrand’s final mission from Luzon to Formosa is an approximate round trip of 3 hours. He performed a perfect “ditch” just off the coast of Cape Bojeador. His aircraft was struck by ground fire while over Formosa, causing a loss in oil pressure. He and his gunner were never recovered.

Bruce Nostrand as he was pictured in a New Jersey newspaper, reporting the ditching of his A-20 Havoc off Luzon in the Philippines in March of 1945.

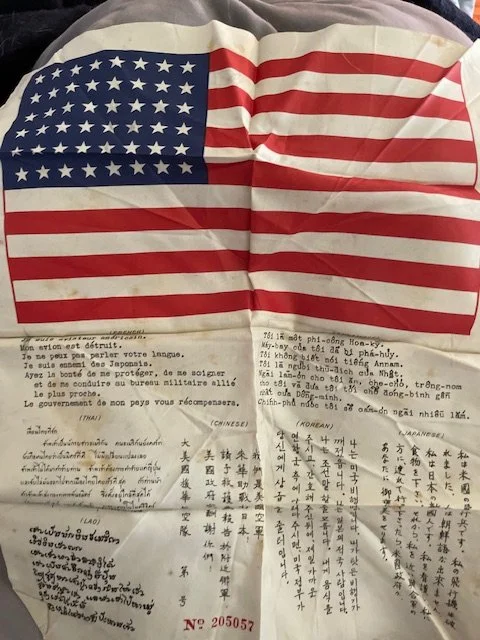

The Nostrand family provided us with a picture of the “Blood Chit” that belonged to Bruce and was returned to them by the U.S. Army. A blood chit is silk cloth that was carried by American airmen promising a reward to locals who helped rescue them if shot down behind enemy lines. The multi-language message identifies the airman as friendly and requested aid for food, shelter and safe return.

This is the Air Medal that was awarded to 2nd LT Bruce Nostrand for his heroic actions during his nineteenth mission, in the Battle of Luzon in the Philippines. He would successfully complete 30 missions in total before losing his life in the South China Sea.

In February of 1945, a letter home was received from Bruce. It stated that “his missions were half over and he hoped to be heading home soon”. But tragically, these words written by Bruce never came to be. On March 2, 1945, returning back to base from the 312th’s first mission over Formosa, 2nd Lt. Bruce Nostrand’s plane went down into the China Sea. Neither the lieutenant nor his gunner was ever recovered.

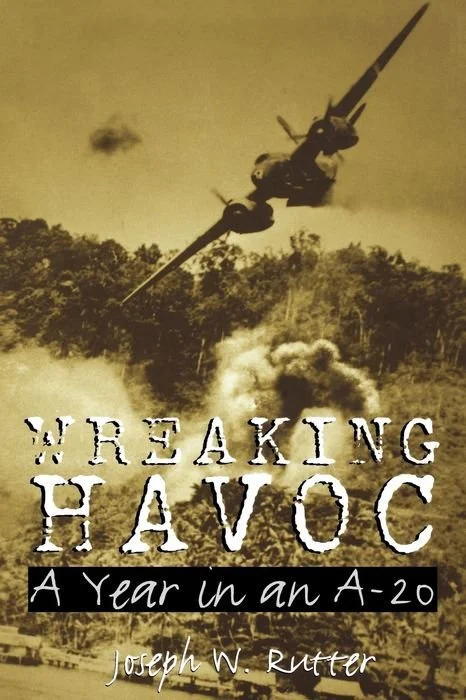

A valuable account regarding the loss of 2nd Lt. Nostrand, his gunner S. Sgt Lyle Thompson, and their plane, was provided by Joseph W. Rutter, the author of the book Wreaking Havoc - A Year in an A-20. Joseph was an A-20 pilot, also in the 312th Bomb Group, who was on the same mission with Bruce on that fateful day. He was an eyewitness to the plane’s ditching.

Returning from the mission to Formosa, 2nd Lt. Rutter heard a radio call on which Bruce was indicating that he was low on fuel, one engine was running rough, and he was planning to ditch near the shore off of Cape Boreador. Rutter said that the sky was clear and he watched Nostrand’s plane settle into the water in a cloud of spray. Bruce had jettisoned the cockpit hatch earlier and the ditching appeared perfect. Rutter was very surprised when he learned that neither Bruce nor his gunner were ever recovered and he offered the following suppositions: “Did Nostrand forget to lock his shoulder harness and hit his head? Did he get hit in the face by the armor glass panel (Rutter was speaking from experience on this option). Had he gotten entangled somehow and thus unable to get out of the cockpit? Did sharks attack them? We would never know”. Two PT boats were at the crash site 30 minutes after the plane went down but only miscellaneous debris was recovered. Natives who had witnessed the crash reported no survivors. Although not stated in the US Missing Air Crew Report (MACR) we have read in two other sources (the book, The Roaring ‘20’s, by Lawrence J. Hickey and Michael H. Levy, and in Bruce’s folder at the Cranford Historical Society) that Bruce’s plane was damaged by ground fire and forced to ditch.

Cranford’s 50th Gold Star

After being notified of Bruce’s MIA status, Bruce’s wife Dorothy waited in Dunellen. His mom Minnie, who had remarried, waited in New Brunswick with her husband, Leon Rowland, and Bruce’s half-brother John, age 17. In Cranford, Bruce’s extended family also waited. For eight long months the family waited for news of their lieutenant, perhaps holding a small spark of hope. But, in November of 1945, Dorothy Hodges Nostrand was notified by telegram that Bruce had been officially declared killed in action. In the newspaper, his obituary bore the title “50th Gold Star” indicating that 2nd Lt. Bruce Nostrand was Cranford’s 50th serviceman lost in WWII. In addition to losing her son, Minnie Erdle Nostrand Rowland had also lost her brother, merchant marine Alfred Erdle, who was killed when his ship was attacked by a Nazi submarine in early 1943. 2nd Lt. Nostrand’s name can be found on the Tablets of the Missing at the Manila American Cemetery. As a decorated pilot in his A-20 Havoc, he performed 30 strafing and bombing missions for our nation.

2nd Lt. Bruce E. Nostrand elevated himself to a respected position in the United States military. He conducted combat missions in a treacherous theater of battle where he flew his A-20 quickly in and out of hostile territory. These bombing and strafing runs were either in support of ground troops or, they left enemy railroads, airfields, barges, roadways and supply depots destroyed, smoldering and bullet-ridden. He and his fellow A-20 pilots did indeed “wreak havoc” throughout the Philippine Islands, and were a key component to victory over Japan.

To tell this narrative, we had the pleasure of working with Bruce’s family members. First cousin Bruce D. Nostrand, and 2nd Lt. Bruce E. Nostrand’s first cousins once removed, Chantal and Tighe Nostrand, provided us with significant historical facts and fondly related personal information to us about their fallen hero. From what we have observed, 2nd Lt. Bruce Nostrand was, and is, loved and remembered through multiple generations and branches of his family. At least three family members were named in his honor and in order to avoid confusion, the family, when referring to their WWII hero, calls him simply “Lieutenant”. We were pleased to be able to add some additional facts to what the family already knew. Additionally, we were very lucky to locate and speak with Bruce Rowland, who is a half-nephew to 2nd Lt. Bruce Nostrand and also a namesake. We invite all Nostrand/Rowland family and friends to join us in Cranford on Memorial Day 2026 when we honor "Lieutenant", Cranford’s 86 and all of our country’s fallen military.

Addendum

Below is additional media relevant to this story.

A walk around tour of the A-20 Model G, the same bomber in which Bruce Nostrand flew his 30 missions.

We used this memoir, written by A-20 pilot Joseph Rutter of Bruce Nostrand’s bombardment group, as a guide in writing Bruce’s story..

100-year-old pilot returns to the A-20 cockpit 80 years after his last flight out of New Guinea in 1945. He made his 50th and final flight 4 months after Bruce Nostrand’s last mission.

An internal tour of the A-20G, in the only A-20 still in flying condition.

Flight Characteristics of the A-20, the official government produced training film from PeriscopeFilm.com.

The Battle of Leyte, one of the largest naval battles in history. Includes the story of General MacArthur’s return to the Philippines, including his famous speech.